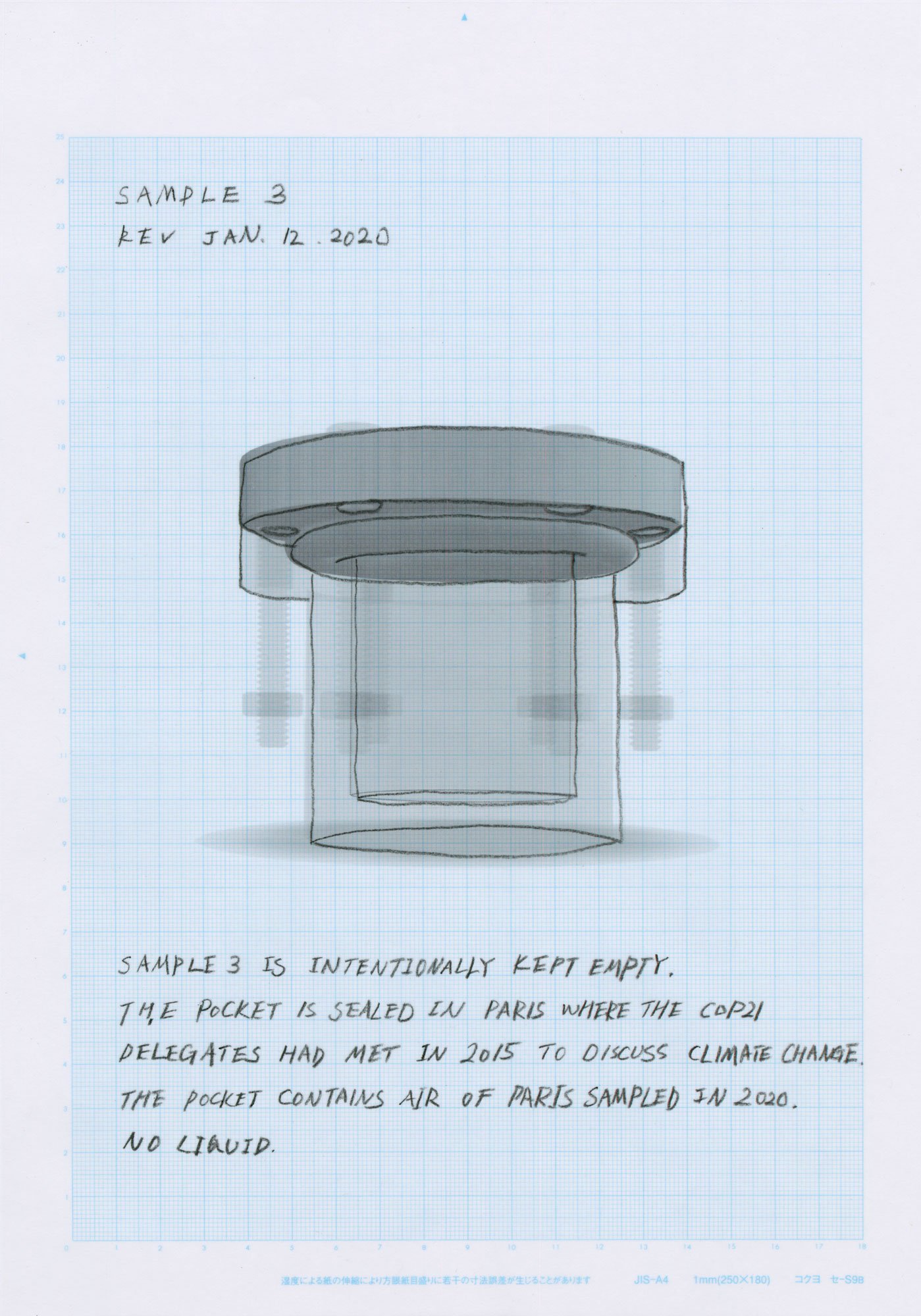

Photo: A Sojourner 2020 pocket in Paris France. Credit: Jonas Cuénin

Nothing, Something, Everything

Ono’s project, Nothing, Something, Everything weaves a vision of Earth’s future climate and our existence within it. A magnetic cylinder—cylindrical in form and always drawn to Earth’s magnetic poles, regardless of its location—serves as a symbol of our deepest longings. Yet at the same time, its opposite end always points away from Earth. A roll of Minox subminiature film, containing the 2016 Paris Agreement and other climate-related documents, reveals more about us than any message ever sent aboard the Voyager spacecraft. A vial of Paris air, sealed in a tiny capsule and untouched by human hands, silently preserves the spirit of the city where COP21 delegates once gathered. Through these offerings to the cosmos, Ono’s project urges us—those who live on this planet now—to look ahead, to inspire future generations, and perhaps even to speak to distant beings who may one day uncover these remnants of our world.

Masa’s work is a magnifier for a too close future where our planet will be unrecognizable. It is a desperate but poetic attempt to hang onto a reality that is changing at the speed of light in the face of worldwide political indifference. Masa is a creator of contemporary artifacts of the future that are in truth laments for our past. His 2020 project for the International Space Station was a brilliant and creative call to celebrate and save what is left of our endangered planet earth, an exceptional exercise in survival, a last minute effort to create a space of resistance, a space of hope.

—Alfredo Jaar

Project I: 1 cc of Paris Air

le dimanche 26 janvier 2020 à Paris, photo: Jonas Cuénin

On my second day in Paris, I awoke at 6 a.m. in what I believed had once been a maid’s quarters in a building on Avenue du Président Kennedy, near Passy Station. As I opened the small window facing the Seine, the aroma of freshly baked croissants and the sight of a bottle of Evian for my morning meal filled my senses. I stretched out my arms and sampled the air, the pocket swinging in the gentle morning breeze, tightly sealed like a precious memory.

At 2 p.m., my photographer Jonas and I met outside Restaurant Le Coq, with Kyoko joining us shortly after. Though it might seem cliché, I felt compelled to capture the Eiffel Tower — iconic and symbolic — as a representation of the industrial revolution that shaped the world we live in today.

Shortly after 3 p.m., we wrapped the shoot, and Maya invited me to a recital. On the way, I shared the morning’s air sample. Laughter erupted as my friends joked about how the ongoing transportation strikes had caused the worst air pollution in Paris. Still, the sight of people carrying baguettes, the delicious cheese, and the music played by my friends filled my heart with warmth. We shared Indian curry, and I returned to Passy. The Eiffel Tower, now dark, cast its shadow over the night.

The first confirmed COVID-19 cases in France were reported on January 24, 2020 — just a day before I landed in Paris. At the time, I had no idea of the magnitude of what was to come.

le dimanche 26 janvier 2020 à Paris, photo: Jonas Cuénin

During our discussion of the project in late December 2019, curator Xin Liu questioned why the air sample had to come from Paris, suggesting that it could just as easily have been taken in New York City. However, I felt that choosing a specific location for the sample carried conceptual significance. I chose Paris — the city where delegates convened for the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21). More specifically, I selected the very site of their gathering as the location for air sampling.

Marcel Duchamp, Ampoule Contenant 50 c.c. d’air de Paris/Ampoule containing 50 c.c. air of Paris, The Guaranteed Surrealist Postcard Series, postcard, print, 1937. Courtesy of Harvard Art Museum