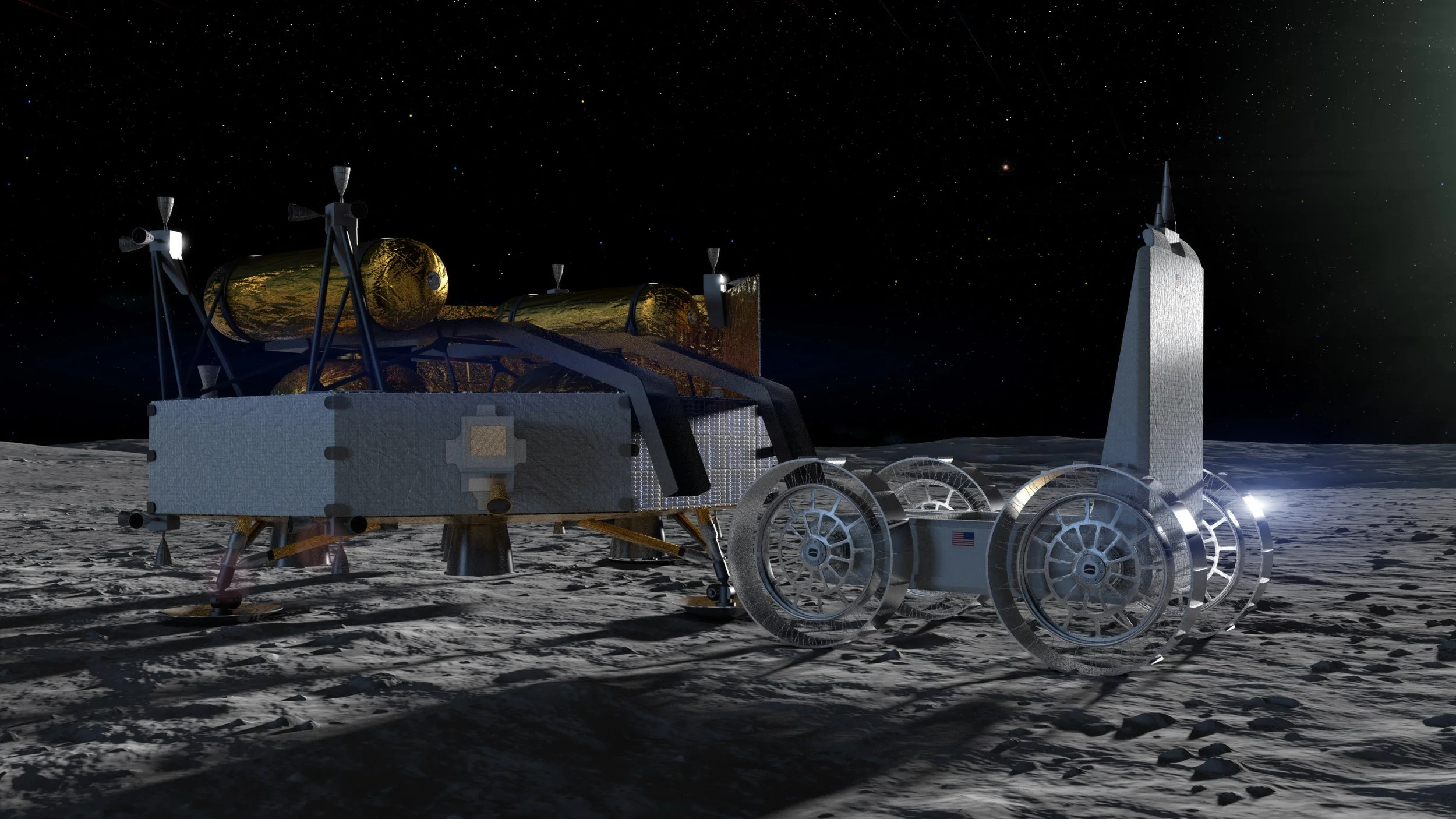

Courtesy: Astrolab

Unfinished (Hope)

As early as July 2026, the Griffin Mission One lunar lander will launch from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A — the very ground from which Apollo astronauts once began humanity’s first journeys to the Moon. This time it is a passage without return. The lander will carry a small rover to the Moon’s south pole, into craters locked in permanent shadow, places where sunlight has never touched and where ancient ice may still endure, waiting to open a new chapter of exploration.

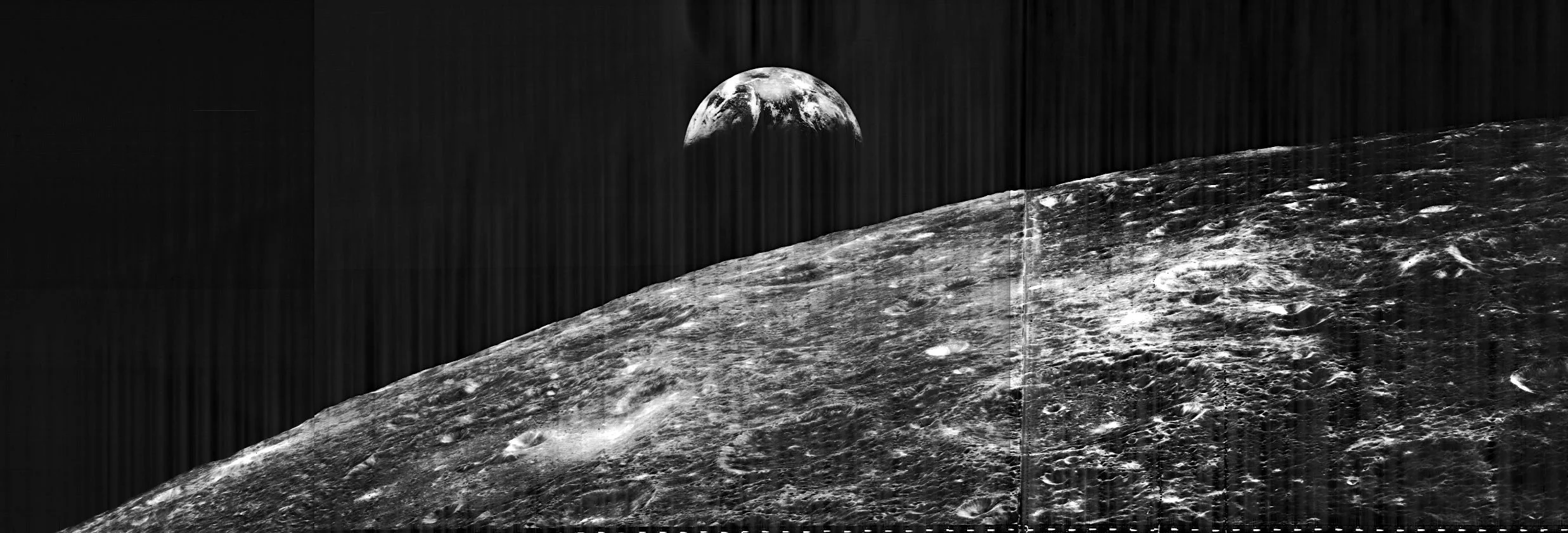

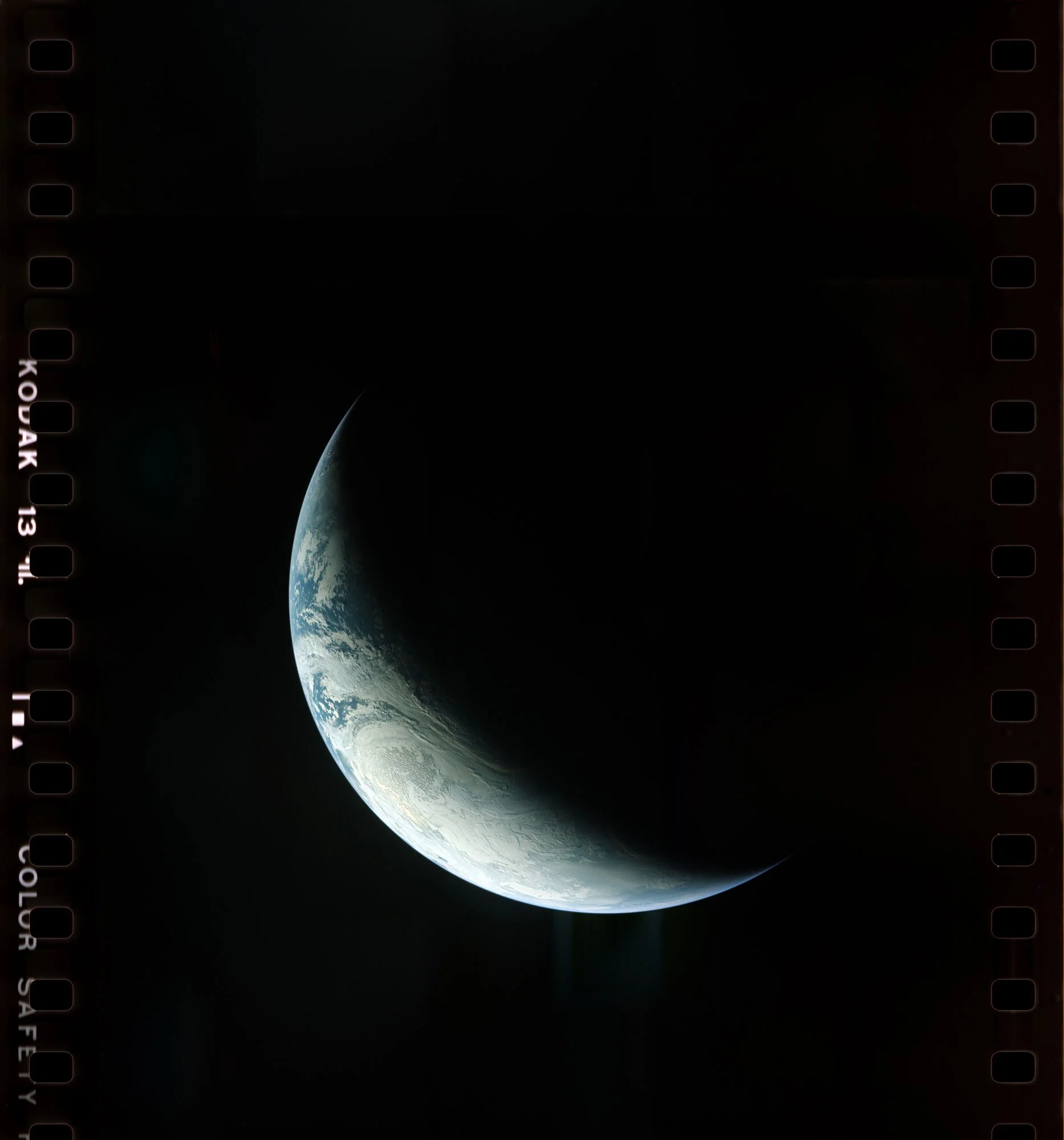

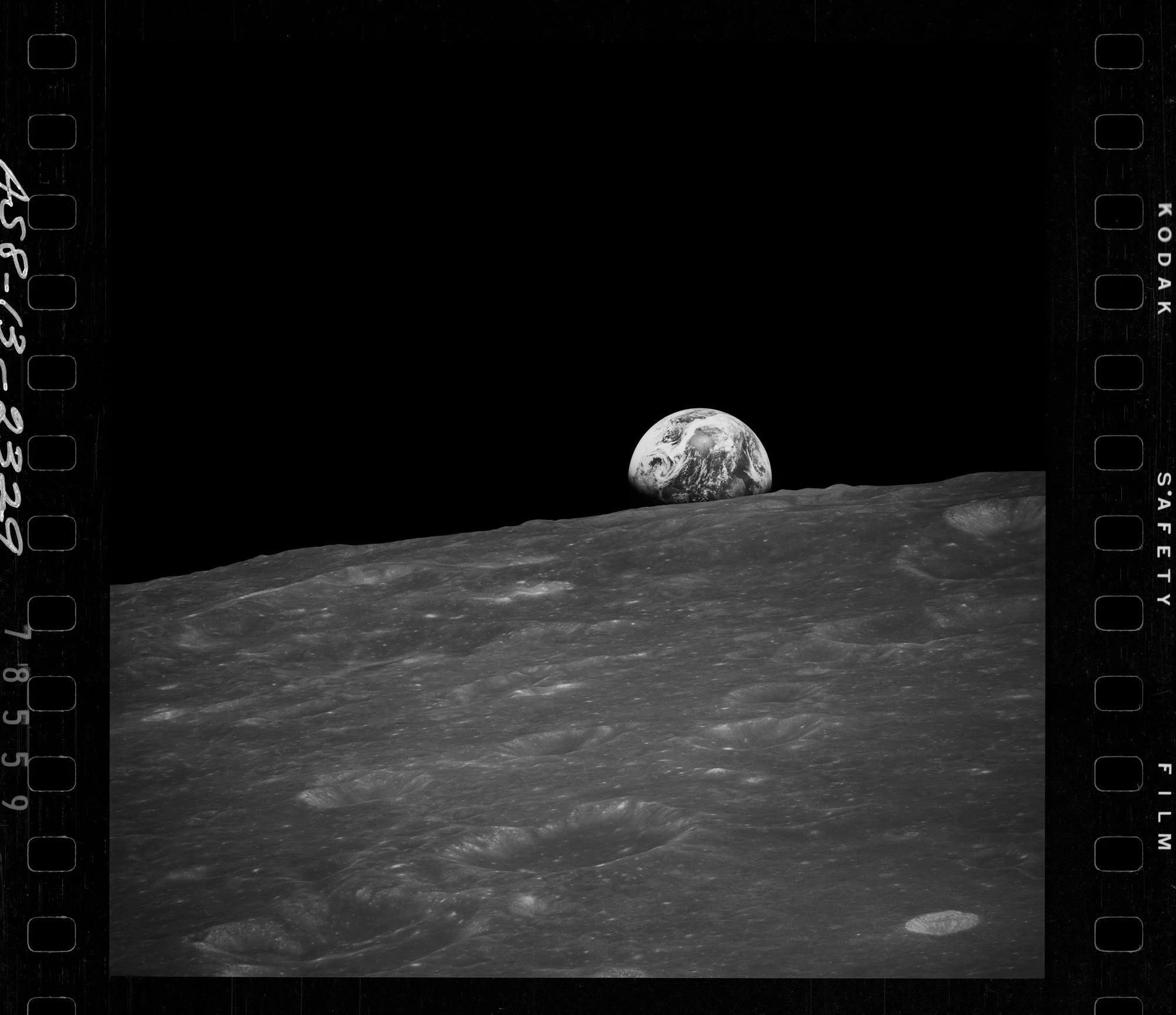

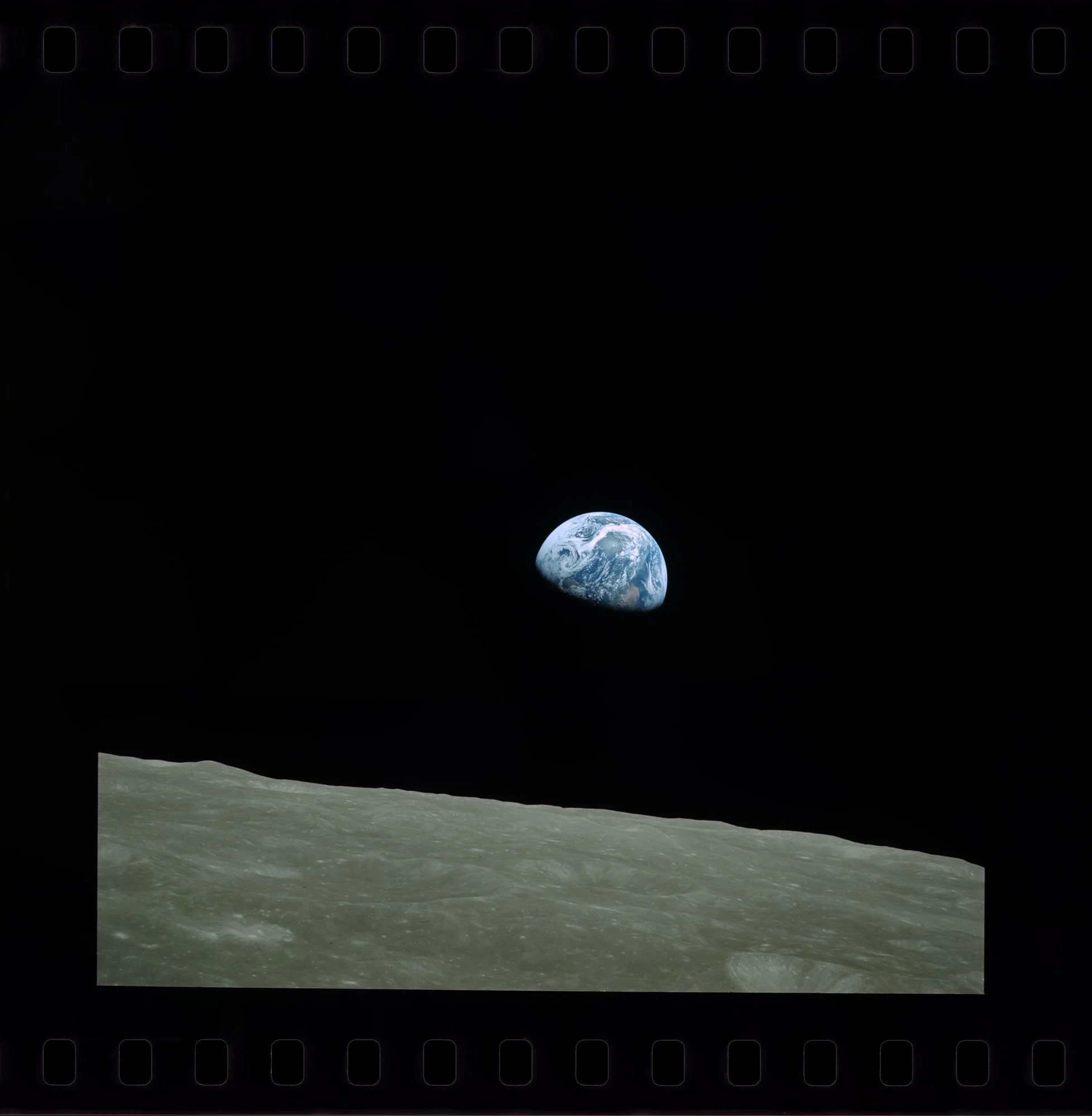

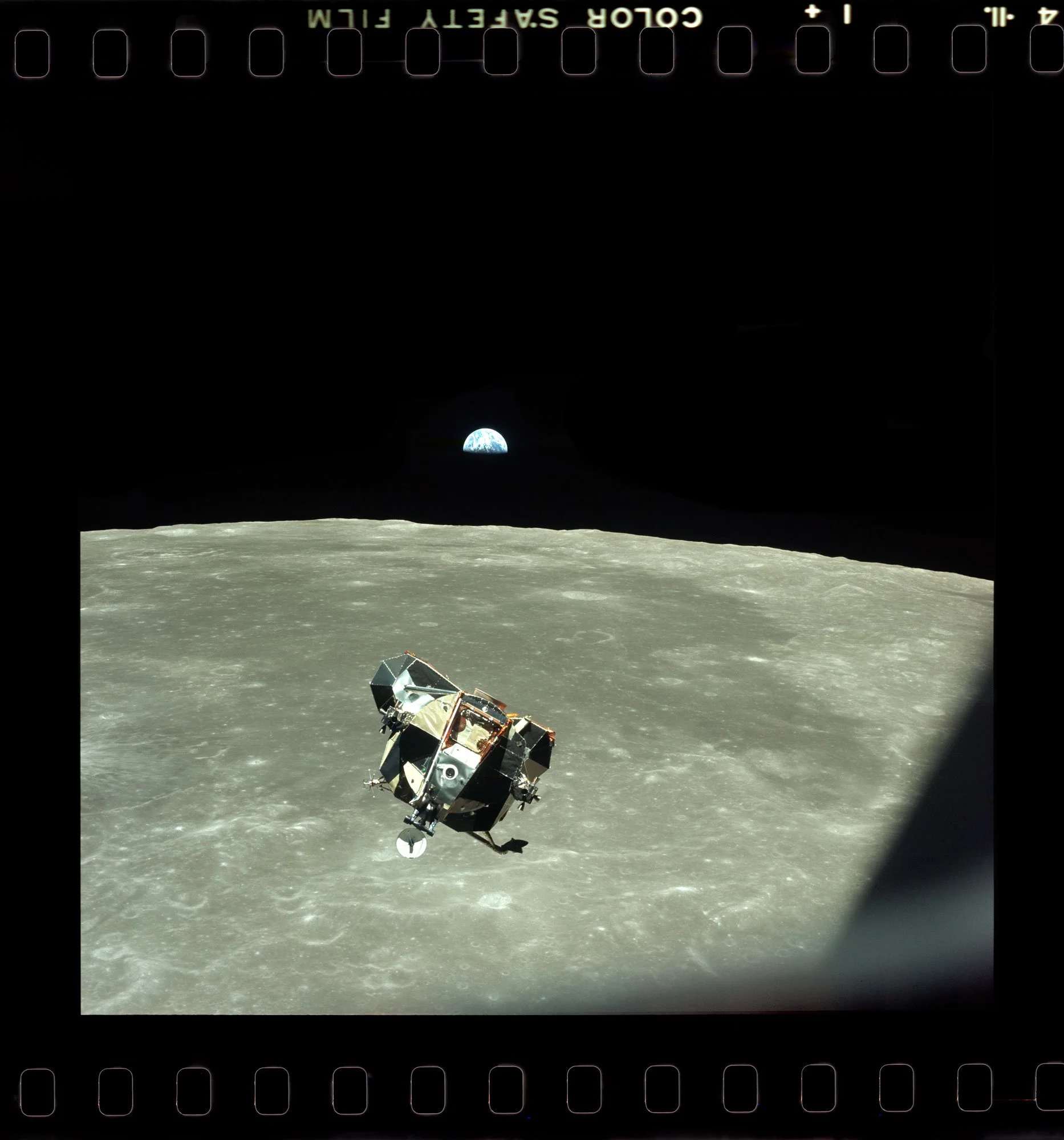

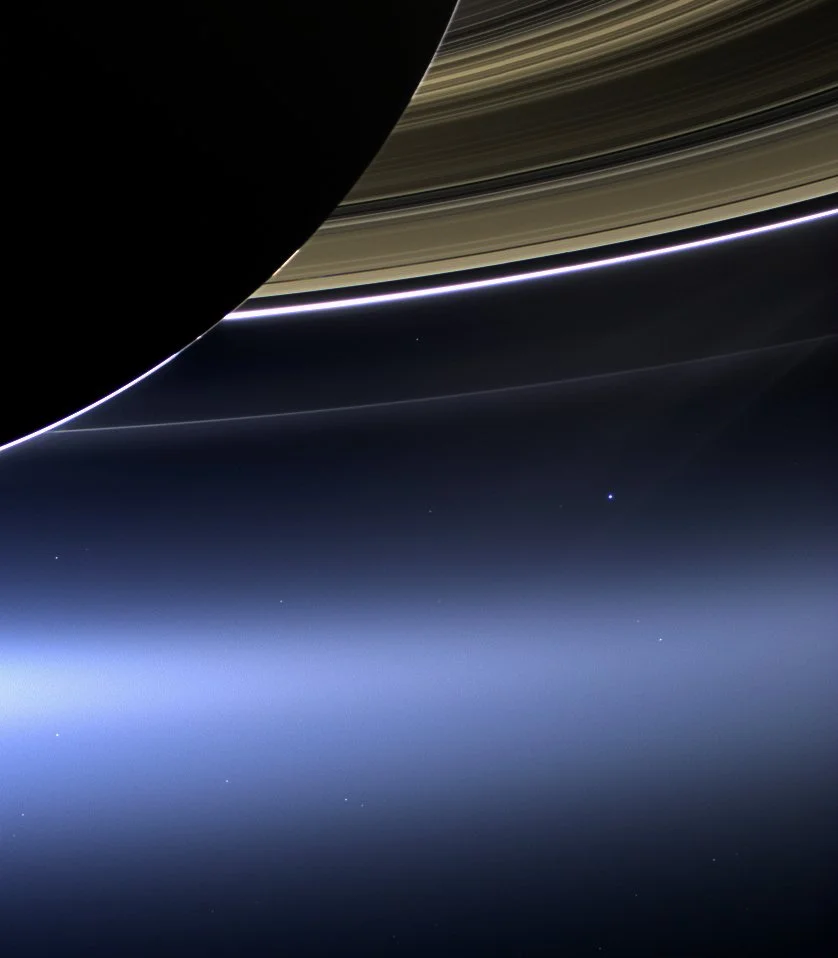

Loaded inside the rover is an art project consisting of fourteen photographs of Earth. Taken over the past half century by Apollo astronauts and others, from lunar orbit and from the far reaches of space, these images changed how we see our world. More than simple pictures of a planet, they revealed the fragile and solitary presence of life in the vast expanse of space.

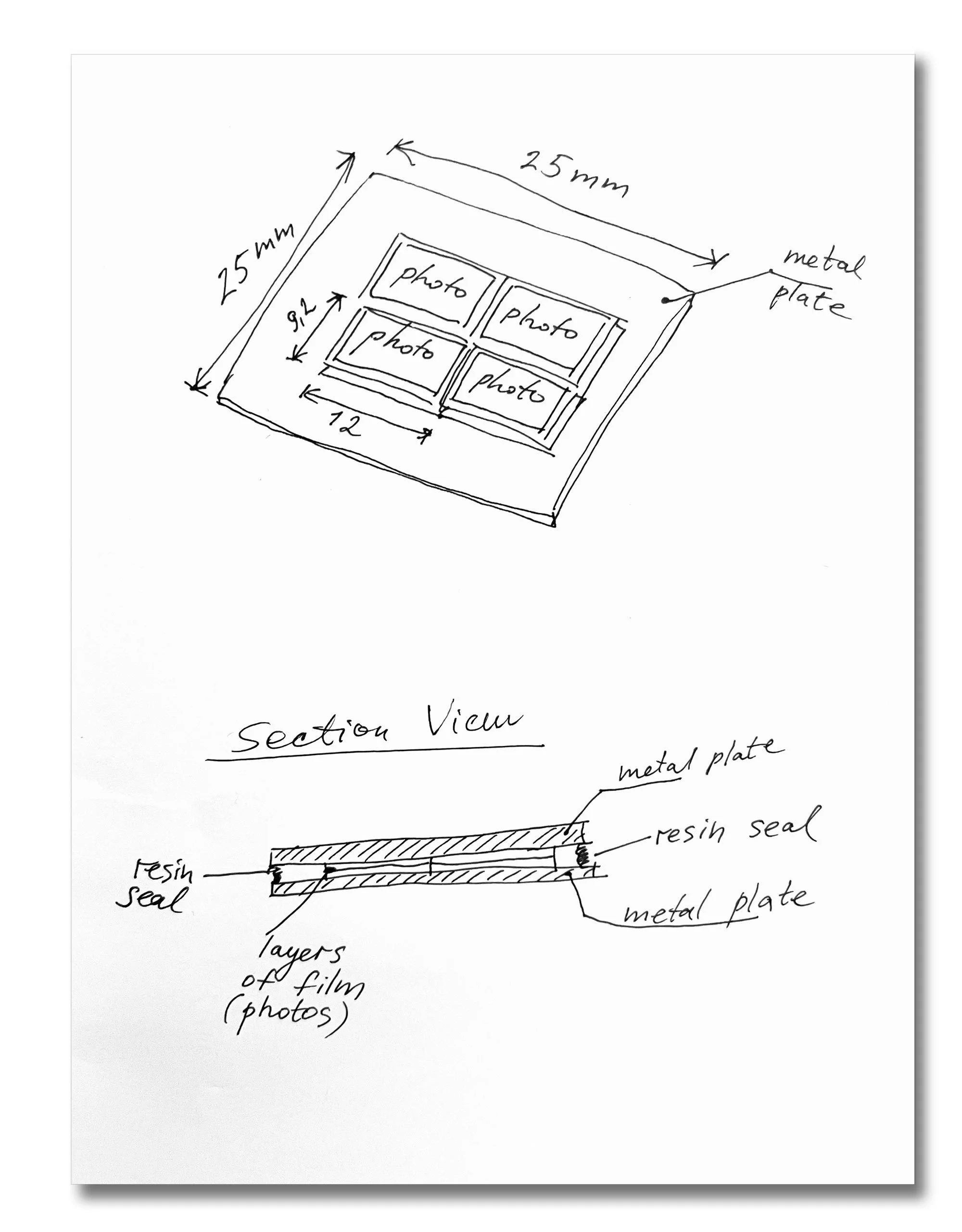

Now more than half a century later for some they will return to the Moon, etched onto Kodak subminiature film. Made by human hands, seen by human eyes, and once cherished by humanity, they will rest in a quiet place beneath an endless lunar horizon.

On the Moon, the chemical bonds that hold these images will weaken. In temperatures that swing from minus 173 to plus 127 degrees Celsius (minus 280 to 260 degrees Fahrenheit), time will erase them grain by grain until the memory they hold is gone. Yet this fading is not an accident—it is the point. It mirrors the fate of all memories, all stories, all civilizations: they vanish. And yet, within this slow vanishing, there is a gesture of hope—that what fades can still be remembered, and that awareness may outlast the image itself.

These images first showed Earth as it truly is: a small, pale dot, alone in the endless dark. They reminded us that our world can break, that the blue we take for granted is delicate and fleeting. Yet their meaning depends not only on what they show, but on what we choose to see, or refuse to see. This project is dedicated to the future generations who will live with the consequences of our actions in the decades ahead.

On the Moon, the film will forget the Earth.

The question is whether we will.

Courtesy: Astrolab